The problematic mulch has been detected as far afield as Nowra, where bonded asbestos fragments were found within mulch in gardens around a newly constructed bridge.

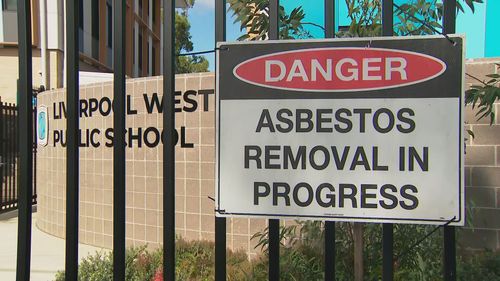

Asbestos has been confirmed at more than 50 locations across Greater Sydney so far, but dozens more are being tested by a new asbestos taskforce in one of the largest-ever investigations by the NSW Environmental Protection Agency.

So just what is bonded asbestos? How did it get into our garden beds? And just how dangerous is it, really?

We spoke to Peter Tighe, the Independent Chair of the Asbestos and Dust Disease Research Institute, for answers.

What is asbestos?

Asbestos is a fibrous mineral which is naturally occurring in Australia as well as other countries around the world.

It was mined extensively in Australia during the post-Second World War years until 1984, and millions of tonnes more were imported from overseas.

Cheap, flexible, extremely strong and resistant to both fire and electricity, it was used in everything from home insulation and fibro sheeting through to hot water pipes, vinyl floor joints and even oven mitts up until the 1990s.

It wasn't until 2003 - decades after its links to deadly lung diseases and cancers were first identified - when the sale, use and importation of all asbestos was banned in Australia.

What makes it so deadly?

Asbestos is made up of microscopic fibres that are easily breathed in.

When this happens, they can become trapped in the lungs, causing two main diseases: asbestosis and mesothelioma.

Asbestosis is a type of lung disease similar to "black lung" or silicosis, which are all caused by different types of dust getting into the lungs.

"As you breathe the fibres into the lungs - especially if you're breathing quite large amounts - it lines the lung and it stops the capacity of the lungs to draw oxygen," Tighe explained.

The lodged fibres will continue to scar the lungs, meaning the sufferer gets less and less oxygen until the increased pressure results in heart failure.

Mesothelioma is a different but equally deadly asbestos-related disease.

It's a form of cancer caused when the asbestos fibres lodge in a person's lungs and work their way through to the lining surrounding the lungs, causing a very aggressive and incurable form of cancer which does not respond well to chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Most people with mesothelioma will not live beyond 18 months from diagnosis.

Even though asbestos was banned in 2003, around 4000 Australians are still dying every year from mesothelioma and other asbestos-related diseases.

The majority of these deaths are related to past exposures dating to before the 2003 ban, but the risks are still present.

How did such a hazardous material get into garden beds?

Exactly how asbestos got into garden mulch all around Sydney and beyond continues to be contested and is the subject of much of the new asbestos taskforce's investigations.

Australia has a huge legacy of asbestos products in our built environment, with an estimated one in three Aussie homes containing some form of asbestos.

Despite this, it's not something you would normally expect to find in garden mulch.

"Mulch is made up of vegetation - it is usually off-cuts from trees and natural products put into a shredder, chopped up and then used as garden bedding," Tighe said.

However, the site which supplied the mulch in question, Greenlife Resource Recovery Facility (GRRF), markets its products as an "eco-friendly alternative" which use recycled materials - such as wood products acquired from building sites.

"When you look at Rozelle (Parklands), chopped-up pieces of bonded asbestos were found, so that (suggests) it has been through the shredder and it's being distributed through their stockpile of mulch," Tighe said.

But GRRF has denied that its mulch contained asbestos when it left its Bringelly processing facility in south-western Sydney.

"GRRF has no control over whether its products are mixed with other mulches, materials or existing soil that has been disturbed," the statement reads.

We keep hearing about 'bonded' asbestos - but what is it?

We have heard from the NSW Department of Health that the asbestos found at all but one of the Sydney sites so far is "low risk", due to it being bonded or "non-friable" asbestos.

This means the asbestos has been bonded into another product - as with fibro cement sheeting - which cannot easily be broken down and released into the air.

Asbestos is considered to be friable if it is in a form that can be easily crushed, releasing the microscopic fibres.

"Friable asbestos is very dangerous, because that generates fibres and you can breathe those in," Tighe said.

This highly hazardous form of asbestos has been found at two locations so far - Harmony Park in Surry Hills and Bicentennial Park in Glebe - with Premier Chris Minns labelling the finds "completely unacceptable".

If bonded asbestos is 'low risk', why are they shutting schools and parks?

"Low risk" is not to be mistaken for "no risk".

We have already established that you really, really don't want to be exposed to the risk of asbestos-related disease, so environmental agencies are obliged to take a very cautious approach - especially when it comes to crowded public spaces like playgrounds and schools.

Moreover, just because the asbestos-containing materials found in mulch are currently non-friable doesn't mean that will continue to be the case.

"This fibro sheeting that went into the mulch stockpile isn't new material - I would hazard a guess that it is probably 50 years old," Tighe explained.

"So that cement bonding would have been starting to deteriorate, so that means when it goes through the shredder it is more than likely to be damaged.

"Once you disturb or deteriorate that bonding agent, the likelihood that it can become friable rapidly increases."

Even if we assume shredding up the bonded asbestos didn't lead to its deterioration - as appeared to be the case in most of the samples that were tested by the environmental watchdog - the risk of the bonded asbestos becoming friable will increase the more it is disturbed.

This could include from heavy weather, such as hail, or from being kicked up by children in a playground.

"So a bonded piece that's not deteriorated - is it a problem? No," Tighe said.

"Should it be disposed of properly?

"Yes, because it can become friable if it's mistreated - and what we've got here is an example of mistreatment."

I think I may have been exposed. What should I do?

There is currently no way to test for asbestos exposure in the short term.

While the risk of having been exposed to a significant amount of airborne asbestos via Sydney's contaminated mulch sites is low, the associated diseases generally take between 15 and 30 years to develop and generally go undetected until the late stages of disease.

Medical research is currently underway to develop a blood test for early detection of asbestos-related cancers, but these are likely years away from becoming publicly available.

How can we stop this happening again?

Tighe hopes the current crisis will prompt a tightening of the enforcement, particularly around the recycling of waste materials such as those from building sites.

"Until we get governments to start a program of encouraging removal by householders and others - giving subsidies and going forward with a program to remove the legacy asbestos in our built environment - we will continue to episodes like this."

https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMihgFodHRwczovL3d3dy45bmV3cy5jb20uYXUvbmF0aW9uYWwvYXNiZXN0b3MtZXhwbGFpbmVyLWhvdy1kb2VzLWl0LWVuZC11cC1pbi1tdWxjaC1zeWRuZXktcGFya2xhbmRzLzYzNDI5ZGYxLWY1MjAtNDE1Ni04NTJkLTExY2I0N2VlYjc4MNIBAA?oc=5

2024-02-25 00:54:43Z

CBMihgFodHRwczovL3d3dy45bmV3cy5jb20uYXUvbmF0aW9uYWwvYXNiZXN0b3MtZXhwbGFpbmVyLWhvdy1kb2VzLWl0LWVuZC11cC1pbi1tdWxjaC1zeWRuZXktcGFya2xhbmRzLzYzNDI5ZGYxLWY1MjAtNDE1Ni04NTJkLTExY2I0N2VlYjc4MNIBAA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Bonded asbestos: How dangerous is it and how did it end up in mulch all over Sydney parklands? - 9News"

Post a Comment